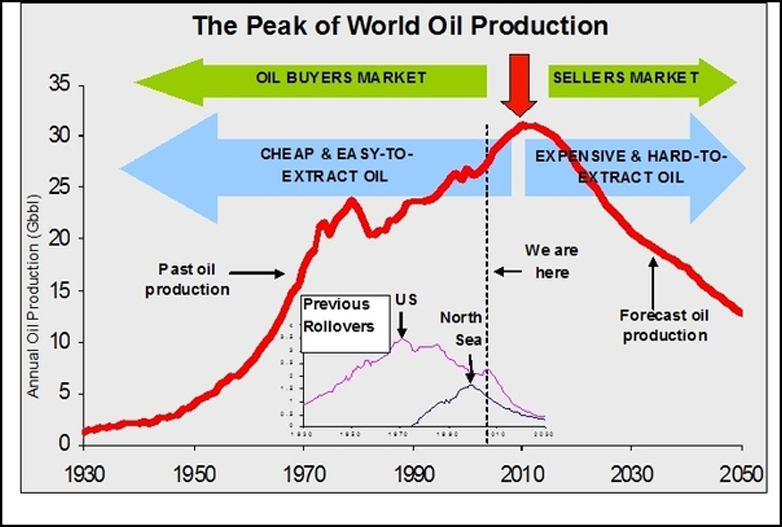

PARIS -- For Total SA, it's all about 95. The French oil giant builds its business with 95 in mind, as if the figure were tattooed on its executives' foreheads. The figure refers to Total's belief, not shared by the majority of Big Oil players, that global production will top out at 95 million barrels a day after 2020. That's only about 10 million more than current production.

Many oil gurus refer to the top-output theory as "peak" oil. Total prefers to call it "plateau" oil, a subtle variation on the theme that suggests production, having reached 95 million barrels a day, will remain at that level for some time in spite of every effort to squeeze more from Earth's desiccated bowels (the peakists think production will fall relentlessly after reaching a peak, which may come well before 95 million).

Peak Oil

Whether peak or plateau, the upshot is the same: Total thinks conventional oil production is approaching its practical limit. That's why Canada and Venezuela figure so large in the company's future. They hold the world's biggest reserves of heavy crude (known as "oil sands" in Canada and "extra heavy oil" in Venezuela). As the easy-to-pump conventional reserves dry up, the thick goo from the frozen north and tropical south will have to fill the gap to forestall a precipitous drop in world production.

At least that's Total's theory.

"We believe that, because of plateau oil, the oil sands are necessary to supply demand growth," said Yves-Louis Darricarrère, Total's exploration and development president.

The company plans to spend as much as $20-billion (U.S.) over the next decade developing its Alberta oil sands portfolio, which was to include UTS Energy Corp., the would-be oil sands developer that in April rejected Total's sweetened $830-million (Canadian) takeover offer, valued at $1.75 a share.

Total has walked away from UTS, whose main asset was a 20-per-cent stake in Petro-Canada's Fort Hills project. But the French company is not giving up on the oil sands. It's just getting started, it says, leaving investors and analysts wondering what it will go after next to add to a portfolio that already includes northern Alberta's Surmont and Josyln projects. OPTI Canada, which has seen its shares triple in the past two months on speculation that it is ripe for a deal, is viewed as a likely target.

Total's belief in an oil production ceiling is not the only factor that sets it apart. Alone among the biggies, it's about to push into nuclear energy and is still keen on alternative energy even as competitors discreetly unplug their wind vanes and solar panels. The company is also a big believer in the chemicals industry.

Total, in other words, is preparing for the day when conventional oil will no longer dominate its energy production. If it's wrong, it will have spent billions on fantastically costly projects - heavy oil extraction, nuclear, solar - at the expense of profit margins. But if it's right, Total has a good chance of emerging as the energy company of the future, one with heavy Canadian content.

CRUNCHING NUMBERS

Among the biggies, Total seems to be a minority of one in its belief that oil production is close to topping out. "They are the only major to come out with the 'cheap oil is all gone' ," said Jim Buckee, the former chief executive officer of Canada's Talisman Energy Inc.

Exxon Mobil Corp., the world's biggest publicly traded oil player, thinks it's highly unlikely that production will reach a peak any time soon. Exxon's position is that that "peak oil" implies that 50 per cent of the oil resource base has been extracted, and that it's impossible to know whether a reserve is really half depleted. Additional drilling and better technology have shown repeatedly that "reserve growth" is possible.

For similar reasons, BP PLC (the former British Petroleum) also rejects the notion of peak oil.

But Total sees the oil resource map differently. It sees demand rising just as the big old fields are losing momentum.

Jean-Jacques Mosconi, Total's senior vice-president of strategy, rhymes off the numbers. The world consumes about 85 million barrels a day. At that rate, we will chew through the proven and probable reserves in 33 years.

The good news, he said, is that the exploration and enhanced-oil recovery, known as EOR, should add another 17 years of consumption. EOR uses methods such as water and carbon dioxide injection to boost reserve pressures. Add it all up and Total figures enough oil remains to keep the planet on the trot for 50 years from today.

The bad news is that, barring a global economic depression, Total expects rising prices because oil companies will struggle to produce more than 95 million barrels a day beyond 2020. The prolific oil fields that turbocharged postwar growth are shrinking.

Production rates in the British sector of the North Sea are falling at 4 per cent year, despite massive amounts of investment in production and reserve technology. Mexico's Cantarell, not long ago the world's second-largest producing field, is dropping at two or three times the North Sea's rate. Total's own production fell 2 per cent in 2008; other companies, notably BP, fell even more.

Henry Groppe, the veteran Texas oil consultant, has said "depletion is endless." Seventy per cent of non-OPEC production comes from seven countries, among them Norway and Russia. Of that lot, only one - Canada - adds production every year. Among the OPEC countries, Saudi Arabia is the only producer with considerable excess capacity.

To this dismal geological mix, blend in political problems. Several countries capable of producing more are perennially stymied by wars, anti-oil terrorism, looting and shabby infrastructure. Take Nigeria, the country with Africa's biggest identified reserves. It is capable of producing three million barrels a day, Total says, but on a good day reaches less than two-thirds of that level.

Put the above- and below-ground constraints together and you have a recipe for high oil prices even before Total's theoretical 95-million-barrel number is reached, at least according to Total. Other companies are more optimistic about production potential and prices, citing technology improvements, the vast shale oil resources in the United States and the potential for more deep-water and Arctic discoveries.

Total doesn't mind breaking from the pack. It is getting ready for the day when conventional oil goes from a majority to a minority of its production.

Heavy oil from Venezuela and Canada will fill the gap, with liquefied natural gas (LNG), nuclear and alternative energy playing supporting roles.

"After 50 years, you will have the big bulk of production from heavy oil," Mr. Mosconi said. "Because we think there is a plateau coming, the world will need all energies, including nuclear."

Total dipped into the Alberta oil sands in 2003, when it bought into Conoco's Surmont project, in which it now has a 50-per-cent stake. Two years later, it bought Deer Creek to gain access to the Josyln project, where Total's interest is 74 per cent. The two acquisitions cost about $2-billion and added about 2.2 billion barrels of reserves to Total's reserve portfolio. In 2008, it paid $541-million for Synenco, which has 60 per cent of the one-billion-barrel Northern Lights project.

Total's oil sands experience has not been entirely happy. Blame collapsed oil prices, rising costs and disappointing technology. Surmont last year produced the equivalent of 18,000 barrels a day, but the project's second phase is on hold because of low oil prices - Total has said it needs about $80 (U.S.) a barrel to make the oil sands work.

"At $40 a barrel, we cannot proceed," said Michel Seguin, Total's director of exploration and production for the Americas.

The bigger problem is Joslyn, where a trial run failed to produce as much oil as expected. Too much water was used to separate the oil from the sand, resulting in an excessively big tailings pond. "The challenge for the mine is to separate the sand from the oil with as little water as possible," Mr. Seguin said.

Joslyn, he said, is "not on hold. But more time is necessary to optimize the process." Still, Total's 2008 annual report, released in April, left a knife dangling over the project, saying: "Both the mothballing of this site's facilities and the possible complete removal of assets from this site are being studied."

In spite of the setbacks, and even though it doesn't expect any significant oil sands production until 2015, Total is not giving up on Alberta.

The province figures so prominently in Total's future that the company is in the early stages of planning a heavy oil upgrader in Edmonton with a capacity of 130,000 to 230,000 barrels a day and a price tag of $5-billion to $10-billion.

RIGHT AT HOME OVERSEAS

Total has always been an odd beast among the big, integrated oil and gas companies.

Throughout its history, it has been closely associated with the French state, even though the government sold off the remnants of its equity stake by the 1990s. Total executives say they consider their company a "strategic" national asset.

Its current CEO, Christophe de Margerie, a noted bon vivant with a walrus mustache, seems to relish his fat-cat status. In early April, when rage about excessive executive pay filled the newspapers, he used a radio interview to argue that there was no point in cutting his pay to satisfy his critics. "Even if I were to cut mine in half, it would still be too big," he said.

"Big Mustache," as he is known in the French press, is fond of long, wine-soaked lunches and is perennially late. He reportedly once arrived nearly two hours late for a meeting with Qatar's oil minister, Abdullah al-Attiyah, and promptly fell to his knees to apologize.

Total was formed in 1924, six years after the end of the First World War, to create a strategic national oil company that could supply the country in the event of another war with Germany.

The new company landed its first significant holding in Iraq: It inherited Deutsche Bank's 24-per-cent share of the Turkish Petroleum Company, later called the Iraq Petroleum Co., as war reparations.

The Iraqi company found oil near Kirkuk in 1927. "Total was born in Iraq," said Mr. Mosconi, the strategy chief.

The Persian Gulf area has always been close to Total. It has had a big presence in Abu Dhabi since the 1930s and, with GDF Suez and other French partners, is now in competition to build a nuclear reactor there.

"We started our operations in countries with a strong historical French link," Mr. Mosconi said.

Total grew by picking its targets with a deft mixture of geopolitics and geology, adding refineries, tanker fleets and developments in far-flung, and often politically unstable, parts of the world, including Colombia, Angola, Yemen and Argentina. The company went from big to enormous in 1999, when it bought Belgium's Petrofina, and it became one of the world's six supermajors a year later, when it merged with French rival Elf Aquitaine.

Total has a market value of about €90-billion ($143-billion Canadian), making it the fourth-largest, publicly traded integrated oil company, and has 96,000 employees. Montreal's Desmarais family, through Power Corp. of Canada's Pargesa holding company, has an indirect, 3.9-per-cent stake in Total.

A FINGER IN EVERY PIE

While other oil giants have little time for energy projects outside oil and gas, Total is charging madly off in all directions. It likes nuclear energy, solar energy (but not wind, which Total says is less reliable) and chemicals.

Total's expectation that mandated carbon dioxide reductions are on the way is one more reason for its push into nuclear.

It admits it knows nothing about nukes and isn't going to bother riding the technology learning curve, but is interested only in building and managing facilities.

The attraction to nukes is also driven by the fact that it has impeccable connections in the Middle East and Africa and experience in managing big industrial projects. It is, therefore, a natural partner for other French companies that want access to those markets. GDF Suez and the French nuclear energy company Areva chose Total as their partner to bid for Abu Dhabi's first nuclear generating station partly because Total is a household name in that part of the world.

"Abu Dhabi feels comfortable having Total in the GDF partnership," Mr. Mosconi said.

A similar strategy drives Total's chemicals and refining businesses.

Saudi Arabia is not keen on foreign oil companies playing in its sandbox. But it is open to foreign petrochemical and refinery investments. Total has 37.5 per cent of a partnership that has bid for the new Saudi Jubail oil refinery, with a capacity of 400,000 barrels a day, on the Persian Gulf. The French hope that any goodwill earned at Jubail will be rewarded with participation rights in other projects, perhaps in oil development.

Since dropping its pursuit of UTS, analysts say Total has no obvious next target in Canada, though Nexen Inc. and OPTI Canada Inc., both struggling in various ways, should not be ruled out.

Some investors think Total will take another shot at UTS. Others think it will bypass UTS and try to buy directly into the Fort Hills project.

Either way, Total will soon have to decide whether to revive the Josyln project and whether to take Surmont to the next level.

One thing is for sure. Total is haunted by the 95-million-barrel plateau figure and knows it cannot ignore Canada and Venezuela. "The big accumulations of oil are only in those two countries," Mr. Seguin said.

***

The Total perspective

85 million

Number of barrels of oil the world consumes every day

33 years

Amount of time it will take to consume the proven and probable oil reserves

$20-billion (U.S.)

Amount of money Total SA plans to invest in Alberta's oil sands over the next decade

$80

Price per barrel of oil that Total says it needs to turn a profit in the oil sands

250,000

Barrels a day of oil production

Total wants from Canada by 2020

15

Percentage of global reserves

Total expects to come from

Canada and Venezuela within 15 years