Again, most oil commentators look at all of this through a purely economic lens. But it may be helpful to think more in terms of thermodynamics. Oil, after all, is primarily useful as a source of energy. And it takes energy to get energy (it takes energy to drill an oil well, for example). Energy profits from oil extraction activities were once enormous, and those energy profits got spread throughout society, wherever oil was used. Now, petroleum’s energy profitability is falling fast.

The peak-oil discussion was an effort to warn society ahead of time: Once the dynamic of declining energy profitability really gets rolling, adaptation becomes much more difficult.

While conventional oil wells 50 years ago often had a hundred-to-one energy payback, for example, today’s bitumen production in Canada shows an energy-return-on-energy-invested (EROEI) ratio of between 3:1 and 5:1. This declining energy profitability is why it’s now so hard to produce oil at a financial profit, and also why — even when oil supplies are still expanding — they don’t fuel as much economic growth throughout the economy.

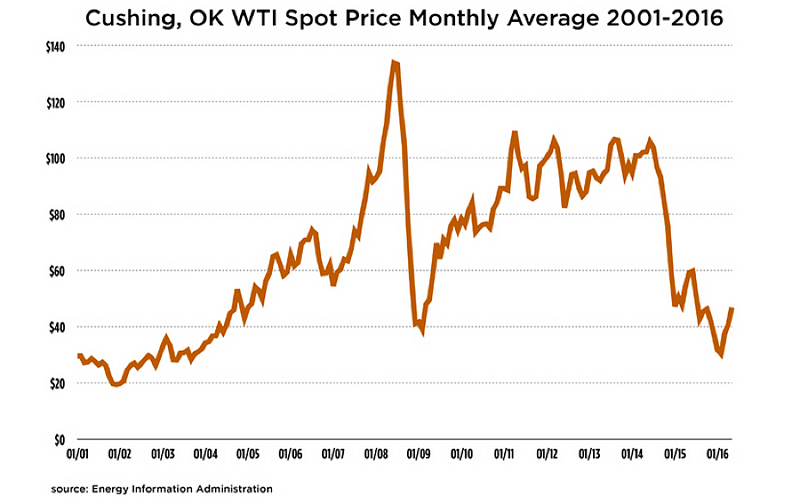

Since oil is the key energy source of modern civilization, the effective EROEI of society as a whole can be said to be declining. It might not be far from the mark to suggest that we are witnessing the early stages of the thermodynamic failure of global industrial society. An earlier phase of the process manifested in the financial crash of 2008; when that occurred, governments and central banks responded by deploying easy money (massive debt, low interest rates) to prop up the system, and this temporarily masked society’s dwindling EROEI. Debt can accomplish this over the short run: Money is effectively a marker for energy, and we can borrow and spend money now on costly energy with the promise that we will pay for it later (hence the massive build-up of debt in the oil industry). But if cheaper-to-produce energy and higher prices don’t emerge soon, those debts will eventually become transparently un-repayable. Hence what is inherently an energy crisis can appear to most observers to be a debt crisis.

The problem of eroding energy profitability is hard to deal with partly because the decline is happening so fast. If we had a couple of decades to prepare for falling thermodynamic efficiency, there are things we could do to soften the blow. That’s what the peak oil discussion was all about: It was an effort to warn society ahead of time. Once the dynamic of declining energy profitability really gets rolling, adaptation becomes much more difficult. Oil no longer provides as much of a stimulus to the economy, which just can’t grow as it did before, and this in turn sets in motion a self-reinforcing feedback loop of stagnating or falling labor productivity, falling wages, falling consumption, reduced ability to re-pay debt, failure to invest in future energy productivity, falling energy supplies, falling tax revenues, and so on. How long can debt continue to substitute for energy before the next traumatic phase of this feedback process begins in earnest? That’s anybody’s guess, but our window for action is likely months or years, not decades.

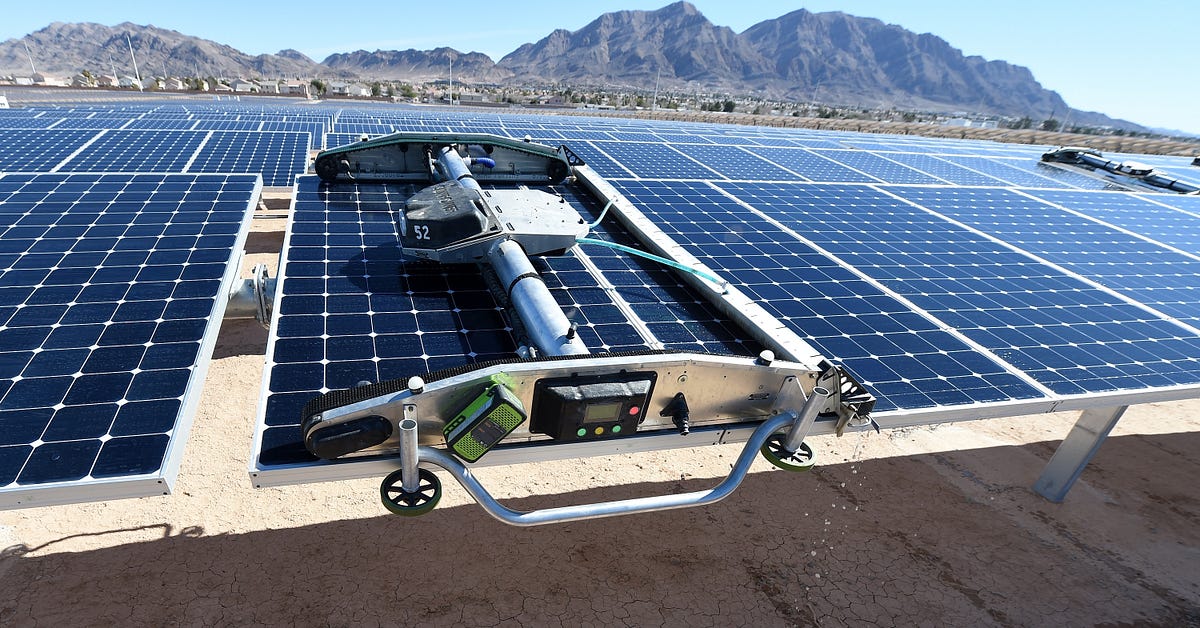

What could world leaders do about declining societal EROEI if they took the crisis seriously? Clearly, part of their strategy would entail building an alternative energy supply infrastructure — which must be low-carbon, since we also face the existential threat of climate change. Indeed, some environmentalists say peak oil is a non-issue because whatever we do to tackle climate change will simultaneously solve our oil dilemma. I’m not so sure about that. Most proposed climate mitigation strategies start with transitioning the electricity sector to solar and wind power, and then proceed with a gradual electrification of other energy usage (electric cars, electric air-source heat pumps to heat buildings, etc.). But, as noted, much of the transport sector is hard to electrify. It’s nice to see more Nissan Leafs, Teslas, and Chevy Volts on the road, but those carry people; our real challenge is moving all the stuff we need (food, raw materials, and manufactured goods of all kinds), and that stuff outweighs passengers by an order of magnitude and currently travels mostly by ship and truck.

We need to build a bridge to the energy future, even while the highway we’re on is crumbling beneath us.

Efforts now underway to power trucking and shipping renewably are woefully insufficient. Peak oil demands that we focus on transport now, not later: We should supply substitute renewable fuels where absolutely needed, but we must also quickly and substantially reduce our reliance on long-distance transport through economic re-localization.

As much as I hate to think so, thermodynamic decline and economic contraction could seriously impair our chances for a robust renewable energy transition in response to the threat of climate change. Building enough solar panels and wind turbines, and adapting the ways we use energy (in building heating, in industrial processes, in transportation, in food systems, and on and on), will take time and many trillions of dollars of investment. It will also require stable international markets and supply chains, and those could be thrown into turmoil by the declining thermodynamic profitability of our society’s current primary energy source — unless we can somehow build a bridge to the future while the highway we’re on is crumbling beneath us.

A few of us never stopped studying the nexus of problems subsumed under the rubric of peak oil, and we now have a more sophisticated understanding of oil production and prices, and links with the larger economy. Still, outside a relatively small, well-informed audience, nobody’s listening — because the subject of peak oil has been discredited following a short-term oil supply glut and low oil prices. Even many environmentalists have filed peak oil under “Things Not to Worry About.” (One high-level climate campaigner of my acquaintance has said that peak oil is a lousy issue to organize around — as though we can afford to ignore a gargantuan problem if it offers insufficient fundraising potential). Thankfully, that small, resourceful audience has taken action anyway, in the form of community resilience-building efforts that often fly under the banner of Transition Initiatives and similar networks.

It may be counterproductive even to use the phrase “peak oil” today, though I’ve done so in this essay. After all, we don’t know if the actual maximum in world oil output occurred last year, or will happen this year, next year, or several years from now. This lack of definitive predictive power is the Achilles’ heel of an otherwise useful term. What instead should we call the complex, interrelated set of developments described above? Should we dub it “the thermodynamic collapse of industrial civilization”? That has a nice techno-apocalyptic ring to it and is probably more accurate. But it has too many syllables and requires too much background explanation. Only geeks could ever get it.

Something is happening here, whether we have a snappy buzzword for it or not. And we can’t afford to ignore it, regardless of how hard it is to explain it to economists, policymakers, and even many environmentalists. My colleagues and I keep trying to do just that. But at this point it also makes sense to batten down the hatches and build resilience close to home.