STAGE one of Saudi Arabia’s plan—or perhaps hope—to restructure the oil market is taking longer than expected. By refusing to rein in production while prices fell, the Saudis permitted a big surplus to grow and served notice on higher-cost rivals (Russia, Venezuela, American shale-oil producers) that they would not prop up other people’s profit margins at the expense of their own market share.

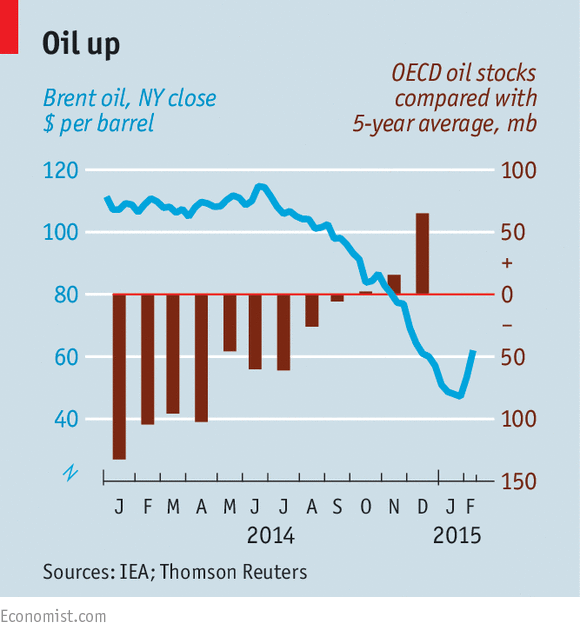

That signal has been weakened by the growing amount of oil in storage, which is absorbing most of the glut. World oil stocks rose about 265m barrels last year and Société Générale, a French bank, reckons they will increase by a further 1.6-1.8m barrels a day (b/d) in the first six months of this year, adding roughly 300m barrels to the total. At the moment, global oil output is exceeding demand by about 2m b/d, so the build-up of stocks is enough to take most of the glut off the market. Oil is being stored in the hope that demand and prices will pick up later. So stocks, plus renewed political worries (flows from Libya’s largest oilfield were disrupted again this week by apparent sabotage), have pushed the price of oil back over $60. After having fallen by more than 60% since June, the price of a barrel of Brent crude closed above $62 on February 17th.

The restocking cannot continue for long. Storage facilities in Europe and Asia are already 80-85% full. Much more and they will overflow. As it is, companies are renting tankers to keep oil in. If storage space runs out, prices could tumble again.

Whether that happens depends on how quickly phase two of the Saudi plan gets under way. This is to force high-cost producers out to increase the influence of Gulf countries. At the moment, this is happening only slowly. Oil types have recently become obsessed with the so-called “rig count”—the number of drilling rigs operating in America and elsewhere. Analysts think that as the rig count declines, shale-oil output will fall, hurting profits and investment. That seems dubious.

Figures from Baker Hughes, an oil-services company, showed that the rig count in America in mid-February fell to its lowest since 2011, and was 35% below its peak in October 2014. That is a big fall. But most of the idled rigs are in marginal areas; the fall has been only 9% in the main shale-oil areas, in North Dakota and Texas, which accounted for four-fifths of the increase in American oil output in the past two years. Moreover, productivity is rising in the remaining wells. Citibank reckons that even a 50% fall in the rig count would allow output to rise this year and turn the average shale firm’s cashflow positive, encouraging investment.

More broadly, says Antoine Halff of the International Energy Agency, an inter-governmental body, “The market sentiment may have changed but the fundamentals have not.” The Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) says its members’ output will rise by 400,000 b/d this year; others think the increase will be greater. Non-OPEC supplies are likely to rise by twice that. Thanks partly to cheaper oil, world demand is rising, but not by much. The IEA reckons demand will be flat in the first half of 2015, before rising by 2m b/d in the second. By most estimates, the market will be oversupplied for a while.

In the long run, there are signs that a restructuring of the market is starting, which could eventually lead to high-cost producers going bust or marginal areas being abandoned. Large oil firms have announced cuts in capital spending of over 20% for this year. BP, for example, will spend $20 billion in capital projects in 2015, compared with $23 billion in 2014. New discoveries are down even more steeply. According to IHS, a research firm, new finds of oil and gas were the equivalent of 16 billion barrels last year, the lowest for 60 years. That will cheer the Saudis.