‘Cause I’m the taxman, yeah I’m the taxman

‘Cause I’m the taxman, yeah I’m the taxmanSHINY new hotels are still going up in the capital of Britain’s oil and gas industry, on the rainswept north-east coast of Scotland. Together with posh shops and clogged roads, they hint at the prosperity that has come to Aberdeen in the decades since oil began to flow out of the North Sea. Recessions have come and gone in the rest of the country, but the Granite City has scarcely been affected.

Now, though, people are worried. Since last June the price of oil has fallen by about 60% to below $50 for a barrel of Brent crude. And it is not only the size of the fall that troubles the 160,000 or so people in the region who rely on the oil-and-gas sector, but also its timing. Most people in the industry cheerfully recall previous occasions when the price disappeared down a well—sinking as low as $10 a barrel in 1986, for instance. The black stuff always bounced back in the end. This time, though, the price drop comes at a time when the industry is already facing an unprecedented struggle for survival.

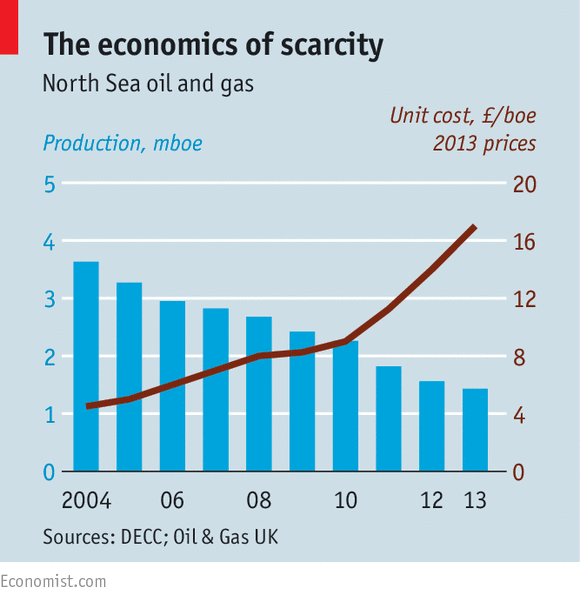

North Sea oil and gas production peaked in 1999, declined slowly up to 2010 and then plunged. Yet the cost of extracting the stuff has risen, and more steeply in the past four years (see chart). The result is that the North Sea is now the most expensive offshore basin in the world. Even the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico are much cheaper to work in than the relatively shallow North Sea. Although about £14 billion ($21 billion) was invested in the basin in 2013 on new production, maintenance and repairs cost a further £9 billion.

The falling oil price has highlighted the thin margins in the North Sea. Oil & Gas UK, the industry lobby group, says that even in good times about 5% of North Sea fields operate at a loss. With oil at $50, almost one-third of the fields will be unprofitable. If the price stays low, it is feared that many of the existing fields will be shut down prematurely, shortening the life of the North Sea.

Little wonder, then, that many in the North Sea business, which still provides Britain with most of its oil and gas, believe that a crisis is upon it. “The industry is in for a very hard time unless we address the high cost structure immediately”, argues Ayman Asfari, the boss of Petrofac, a large oil-services company. The North Sea is a mature basin, with ageing platforms and pipelines that require ever more and more expensive maintenance, so it is only natural that costs will be a bit higher than elsewhere. But the industry also got too “fat and happy” during the good times, as one industry executive puts it, and this has become unsustainable. The average salary in the industry is £64,000, much higher than the national average of £27,200. Offshore workers now work for two weeks straight and then get three weeks off, whereas a while ago they worked and relaxed in equal measure.

The fall in the oil price is hastening changes that were long overdue. Oil producers and oil-services companies are quickly trying to become more lean and efficient. Petrofac is on a cost-reduction drive; it cut rates for contract work by 10% last October, and will do so again at the end of this month. Britain’s biggest oil company, BP, has sold off some of its smaller, more expensive fields. At the peak of operations in the whole of the North Sea it was producing about 900,000 barrels of oil a day. Now that figure is down to just 160,000, although it may rise again when a new field opens. On January 15th it cut 200 office jobs at its headquarters in Aberdeen, together with 100 contractor jobs. The head of BP North Sea, Trevor Garlick, says that as most of its work is carried out by oil-services companies on contract, he will now be looking to them for “help” on costs.

The government has been urged to cut the high taxes on companies working in the North Sea. It is hoped that this will encourage more investment in exploration and prolong the life of the less viable fields. George Osborne, the chancellor of the exchequer (pictured), who slapped the industry with a surprise tax rise in 2011, promised a parliamentary committee on January 20th that he will do this. But a bigger question is whether the industry can reform itself enough to remain globally competitive regardless of what happens to North Sea production, which will eventually tail off whatever happens to the price.

For Aberdeen has become a global hub of operations, especially in the oil-services sector. Many foreign as well as British companies are based there, running business not only in the North Sea but much farther afield, in West Africa and Central Asia. In 2012 the oil-services sector generated £20 billion worth of revenue in Britain, and a further £15 billion in export of goods and services. Speculation abounds in Aberdeen as to whether many of these high-value, specialist companies will migrate to be nearer their remaining operations if North Sea production peters out. Bringing down costs now, though, would go a long way towards forestalling that.

www.economist.com/