|

|

|

|

|

By Ben Casselman

41%: The percentage of U.S. oil consumption that came from imports from January to October 2012.

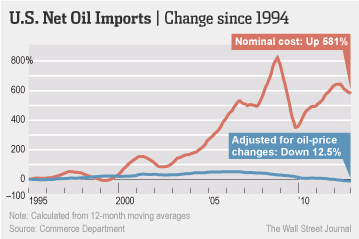

U.S. net oil imports are down 21% in the past two years. Unless they’re up 14%. It depends on how you measure — and therein lies a critical distinction in understanding the rapidly changing U.S. energy picture.

On Friday, the Commerce Department reported that, through November, the U.S. had imported $386 billion worth of oil and petroleum products in 2012 and shipped $112 billion worth overseas (mostly in the form of diesel fuel and gasoline), for a deficit of $274 billion. That’s a bit better than the $299 billion deficit recorded through the same point in 2011, but up 13.8% from 2010.

News of rising oil imports might come as a surprise to readers who have been tracking the surge in U.S. oil production, which was meant to reduce American dependence on foreign oil. And indeed, it has: Through October, the U.S. had imported 41% of its oil in 2012, down from 60% in 2005. New government projections this week predicted imports will make up just 32% of demand in 2014, which would mark the lowest share since the mid-1980s.

How can imports be both rising and falling at the same time? The answer is price. In terms of barrels, U.S. oil imports are falling rapidly due to increased domestic production and flat demand. But prices — especially the global Brent benchmark that’s relevant to most overseas imports — have risen over the past two years. So we’re importing less oil, but each barrel costs more.

Both numbers matter, but for different reasons. For the economy, what matters most is dollars, not barrels. On a short-term basis, a $10 shift in oil prices is going to have a much bigger impact on the trade deficit than the gradual rise in domestic production.

Beyond buddying up with the Saudis or trying to calm tensions with Iran, however, the U.S. can’t do much about oil prices. The recent oil boom has been impressive, but it’s a drop in the bucket in terms of global production, and rising Chinese demand for energy is more than offsetting the stagnation in U.S. oil consumption. So better to focus on what the U.S. can control, at least to some degree: imports. The less oil the U.S. imports — whether because of increased production or decreased demand — the less vulnerable the economy will be to rising prices. A $10 rise in oil prices still hurts when we import 40% of our oil, but not as much as if we still imported 60%.

Over the longer term, though, it’s a mistake to think of volume and price as independent of one another. One of the key drivers behind the recent surge in domestic production has been high prices, which made it worthwhile for companies to pursue expensive, hard-to-tap oilfields in places like North Dakota. Similarly, high prices have helped constrain American’s oil consumption, leading many families to cut back on driving and buy more fuel-efficient cars. A brief dip in prices likely won’t have much effect on either trend, but a more prolonged drop would likely lead to less drilling and more driving — making us more dependent on foreign oil.

In terms of the trade deficit, then, the best thing might be for oil prices to do what they’ve done for the past year: stay more or less flat. At around $100 per barrel, oil is pricey enough to spur drilling and conservation, but not rising so fast as to offset the benefits of reduced imports. Whether prices will remain so cooperative, of course, is anyone’s guess.